Ahead of its next outing Hyper-Possible in 2021, Coventry Biennial is continuing its excavation of the city’s recent intellectual and artistic strata, by screening The Otolith Group’s 2003 film Otolith 1. This film-essay short is being shown in bookable, very conscientiously socially distanced screenings, at the Cathedral’s Chapter House between 14th and 20th August 2020.

I took the train over to Coventry for a showing on the Friday lunchtime. My first proper part-daytrip of this type, for about six months. I first became aware of the Biennial last autumn-when the 2019 festival was underway-and I was temping at the University of Warwick. I very much liked what I saw of The Twin, which drew heavily upon the connotations of Coventry’s town-twinning relationships, and what they signify about peace, war and a medium sized city in the English midland’s place in the early 21st Century.

So, I was very excited to hear that the next iteration of the Biennial, coinciding with Coventry’s year as City of Culture in 2021, is focused on digging into the city and its hinterland’s seam of rich recent intellectual and cultural innovation. Sifting through and interrogating the rich resource layed down and formed by Art & Language, The BLK Art Group and the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit (CCRU) so as to create new works and dialogues which integrate those hallowed collective’s thought and practice to forge something which speaks to and resonates with Coventry today.

Screening Otolith 1, which has been purchased by the Arts Council to form part of their national collection, ties into the city’s connection-via the University of Warwick-with the CCRU. The film’s creator, social anthropologist Anjalika Sagar, was along with fellow founder of The Otolith Group Kodwo Eshun, affiliated for a time with the CCRU. A clear sense of intellectual connection with the work of the CCRU, seeps through the film in its asking of overarching questions about the human race’s future and how the past, present and future is mediated by our relationship to technology.

From a historian’s perspective watching the film today is fascinating. The narrative it presents uses a blend of footage shot in 2003 (when the film was made) and archive film from across the 20th Century and-courtesy of some entirely fictional elements-spans around 200 years. It encompasses a few months in the life of Anjalika Sagar in 2003, whilst she was making the film, the life of her grandmother who was a key intellectual and political figure in the Indian Communist Party throughout the 20th Century. Their lives are drawn together in a historical narrative woven in the year 2103 by a woman descendent of theirs not yet born, and not due to be born for decades to come, who is a scientist and through an unfortunate side effect of space travel is unable to live on earth so must remain in space.

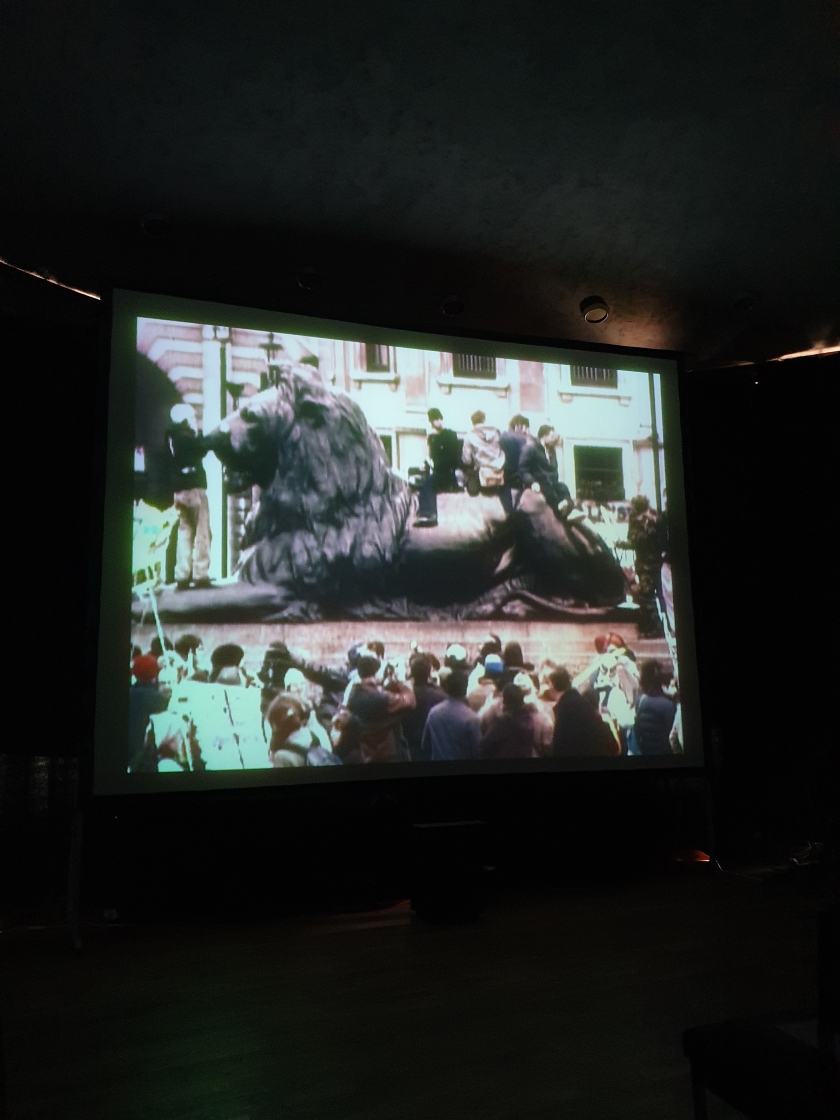

Much of what the film explores, such as whether even today when we remain tethered to our planet, we can “know the world… except through media”, remains as pertinent a provocation as it did nearly 20 years ago. With other aspects of the film it is interesting to view it and think about what has changed and why. A fascinating period detail is the section early in the film when Anjalika focuses upon the climate in the early spring of 2003 in the run up to the Iraq War. She talks over footage of a demonstration, that today is as far away from our current moment as the Miners Strike (1984-85) was from hers, about the participation of her and those around her in the mass protests against the war. In the narration which accompanies a montage of the protests, which today do look about as distant as Grunwick and the March for Jobs, she speaks of “everybody [knowing] that America was going to invade Iraq… Yet 1.5million marched anyway… A protest for freedom of speech” a simulacrum of a demonstration as if those opposed to the war felt a deep seated, primeval urge to oppose the war, even if they were sure it would be ineffective. This narrative and framing indicates a reflexive and deep seated sense of postmodernity, of stability and stasis, that both present and future are likely to be much like today, so protests and marches merely an enactment of older established forms.

This contrasts strongly with her Grandmother the Indian Communist’s story, and the interlocking and occasionally overcrossing life of Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman in space. The sections of the film which touch upon Anjalika’s memories of her Grandmother’s anecdotes, about Moscow in the 1930s when (despite the increasingly icy chill of Stalinism) it could claim to be the capital of world revolution. Through the birth pangs of the Indian nation in the late 1940s, despite the shock of the murder of Ghandi, and the violence and displacement of partition. Onto the peak of her Grandmother’s career (seemingly as some kind of academic) in the 1960s and 1970s when a maturing socialist Indian state-for a while at least-appeared to be charting a course alongside other similar nations towards a free, equal, less western dominated world, in which want and iniquity had been eliminated.

This world-unlike Anjalika’s own-is a modernist one of change and possibility, as represented by the success of the space programme in the Soviet Union, and the formal equality enjoyed by successful women like Valentina Tereshkova and the Grandmother herself. It can also, however, with its show trials and political assassinations, be a dangerous one, unlike life in Britain or comparable western countries in 2003. In 2003 the horrific, violent aspects of politics and change, things which can destroy lives and physically tear people apart, have been more or less displaced onto countries like Iraq which are on the periphery of the global system. This is because imperialistic countries like Britain which are at the core of capitalism have fully reasserted themselves, and banished the ghosts of Third Worldism and Soviet style state socialism which once challenged them.

Today: following the crisis of 2008, amidst increasing obvious galloping climate breakdown, the organic challenge to decrepit western liberalism emerging from within capitalism represented by the interests coalescing around political figures like Donald Trump, and now the shock of the Covid-19 pandemic, it is impossible to recapture the hopeless, sedate, dreamlike “end of history” moment within which Otolith 1 was created. Indeed, the rocky world we are entering with all of its pitfalls and potentials is rather more like the eras experienced by Anjalika’s grandmother than the placid, flaccid New Labour era which began with the CCRU at its height, and degenerated into the cynical horror of the “War on Terror”, with the hideous violence unleashed on Iraq at its blackened heart.

This said, despite the bright shoots represented by the creative strategies for resistance and change inherent in the Black Lives Matter, Youth Climate Strike, and emerging sections of the labour movement like the Wetherspoons, cycle courier and “3 Cosas” strikers, in many ways the ghosts of the early 2000s remain with us. Despite new generations, and newly mobilised sections of the population becoming increasingly insistent and forceful in their demands for change, in many ways the seemingly impossibility of actually changing anything, or striking a proper blow against “capitalist realism” (to deploy a term developed by another CCRU alumni and adjacent figure, Mark Fisher) and then rush into the gap left by it, remains as difficult to meaningfully achieve as in 2003. Despite a desperate situation and moments of seemingly real forward momentum it can all too often seem like we’re still chasing after a simulacrum of a political movement and the necessary radical change.

Today it seems on the one hand easier to find the language within which to name, critique and propose substantial changes to the dominant system of relations. On the other, whilst there are plenty of valiant attempts and plenty of exciting collective cultural and intellectual endeavours, it would seem even harder than ever to get substantial and sustained institutional backing to create something like the CCRU. Perhaps the moment of that kind of institutionalised collective has passed, so the challenge is to create something to take its place?

I found Otolith 1 a very exciting and stimulating film to watch and think with. I look forward to the next part of what Coventry Biennial presents and creates on their journey into the Hyper-Possible.

Otolith 1 is showing daily on the hour (10:00-15:00) until 20th August 2020 in Coventry Cathedral Chapter House (CV1 5FJ). If you’d like to attend you can book a slot (maximum 8 per screening) here.